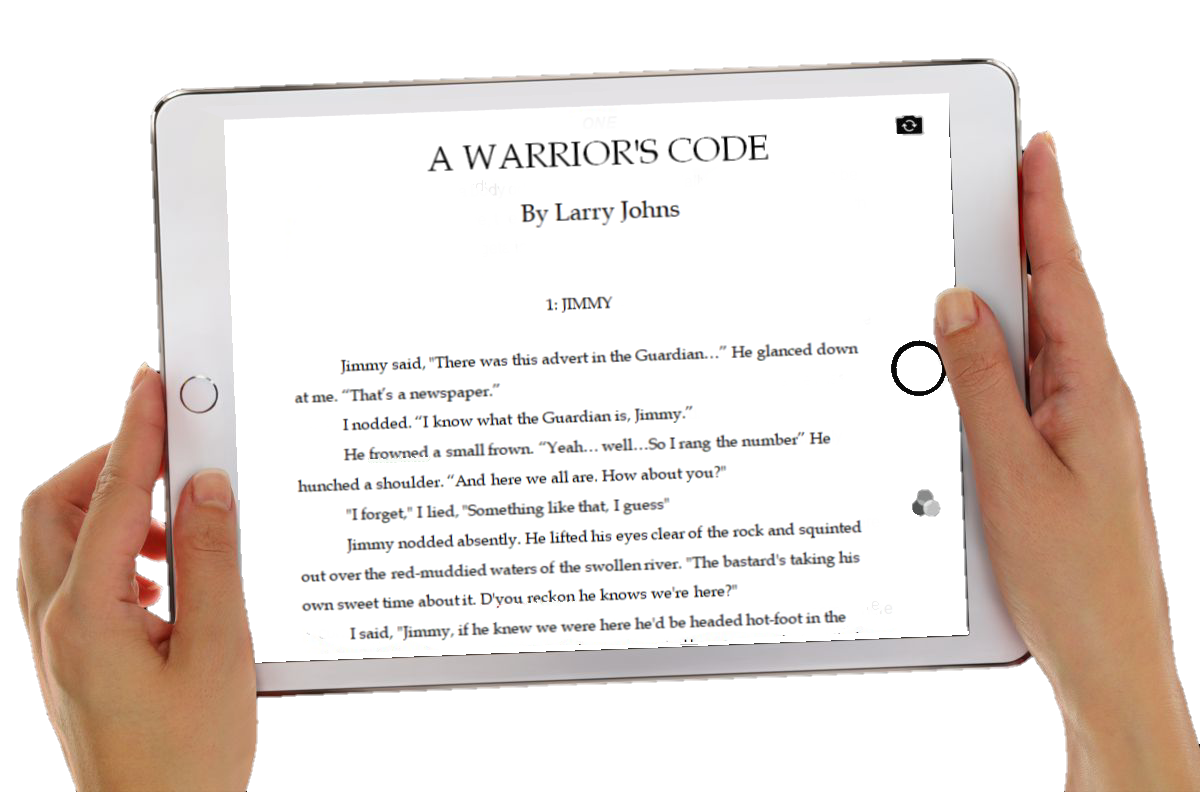

Jimmy said, "There was this advert in the Guardian…” He glanced down at me. “That’s a newspaper.”

I nodded. “I know what the Guardian is, Jimmy.”

He frowned a small frown. “Yeah… well…So I rang the number” He hunched a shoulder. “And here we all are. How about you?"

"I forget," I lied, "Something like that, I guess"

Jimmy nodded absently. He lifted his eyes clear of the rock and squinted out over the red-muddied waters of the swollen river. "The bastard's taking his own sweet time about it. D'you reckon he knows we're here?"

I said, "Jimmy, if he knew we were here he'd be headed hot-foot in the other direction!"

His open face cracked in a self-conscious grin. "Oh, shit! O'course!"

Jimmy would swear like the trooper he used to be. But I was warming to him. His swearing, unconsciously and sometimes impossibly woven into his conversation, had a defensive ring to it. Also, he was a man without serious pretension, and that sat well with me. "So what were you into before you answered the ad?"

Jimmy shrugged. "Sod all! Ligging about like a pratt out of water…when are we going to take him?"

I took a look for myself. Thomas Kamerhi was still a good three hundred yards short of the river, which put him at least fifty yards long of our effective range. And Jimmy was right; he was not hurrying. Then again he was not exactly taking his time, either. He was being careful. And why shouldn't he be careful? He had everything to be careful about. I lowered myself back behind the rock.

The heat was pitiless. It was hot enough to melt leather. A lack of pity is fundamental in Africa. I said, "When he reaches that bush like an upside-down steam roller…see it?"

"Yeah," he said grittily, adding, "You or me?"

I thought about that. Then I thought about the lost camera, and how it altered the entire perspective of the job. I wondered if Jimmy had added up the numbers. Probably not. Jimmy was not paid to think. I, on the other hand, was paid to do just that. The shot, for several important reasons, should have been mine. I said, "Are you good enough?"

Jimmy grunted. "You're damned friggin' right I'm good enough! You just friggin' watch me!"

Jimmy's vocabulary of swear words was limited; probably a reflection of what was uppermost in his mind. Though "frigging" would not have been the way he usually couched it. I wondered why he was coding it now. I also made up my mind about the shot. I was on the spot as a back-up if it all went wrong. I nodded. "You, then, and we'll see. One bullet earns you free beers for a week. It takes you two or more, you stand me for a month. Okay?"

Jimmy grinned down at me again; except that this one was open and full of humour. He'd been all grins and swear words since we'd left B-Company compound three days ago. I did not like many people. Myself least of all. But Jimmy was definitely growing on me. He did not seem to have the vicious streak frequently apparent in most mercenaries. That’s not to say he did not have one. It could be that I had yet to see it. However, he didn't stand a cat in hell's chance of stopping our man on a permanent basis; not with a single bullet. Not at that range. That kind of accuracy requires a whole lot more than enthusiasm.

Jimmy was not in my platoon, and I had yet to witness him shoot at anything; let alone a living target. And a two-legged one at that. I had selected him for this operation because, as far as I was aware, he had never seen, or even heard of, Thomas Kamerhi. Whereas any one of my own platoon would have recognised the man in a thick fog, at any distance. And Chang, for his own reasons, needed this job to happen without it actually happening. Also, Jimmy had not been with the company long enough to have been corrupted beyond his job. At least I hoped both these assumptions were true. But if he was possessed of that degree of shooting skill I would have gotten to hear about it from someone. So I was damned certain he was not going to collect on his beers. In all conscience, I should have quit buggering about and taken the shot myself, taking Kamerhi out cleanly. We were not in the torture business, as Chang was at pains to keep reminding us. But it was too damned hot and I was smitten with lethargy; which vaguely constitutes a reason, certainly not an excuse.

Jimmy said, "Where d'you want it?" He was studying the approaching man through slitted eyes.

I knew what he meant but felt like being obtuse. "Where do I want what?"

"The friggin' bullet!" he grated, frowning down at me. His thick, jet-black eyebrows joining in the middle.

I smiled. "What is this…a side bet?" It was also pleasing that he wasn't calling me sir, or Captain Palmer. Military protocol, even pseudo-military protocol, had its place. But this was not the place. I'd asked him to call me Martin, at least for the duration of this affair. But he wasn't actually addressing me as anything. Not that I could remember anyway.

Jimmy shook his head and sweat flew in all directions. "Nah! I just wanna know where you want the friggin' bullet!"

I couldn't help but chuckle. "Well, I don't want it anywhere…but our man needs it just left of his breast pocket. Imagine your bullet is a medal and you're pinning to his chest. That's where I want it!"

Jimmy looked thoughtful for a moment, as if reconsidering the whole thing. "Not a head shot?"

"No, Jimmy. No head shot. Slap bang in his heart." This was the crunch. Would Jimmy figure it out, or would he not. Would he figure out that a miss-placed head shot could make identification impossible? As a smokescreen, I added, "It's the bigger target anyway." I was treating it as a game, and I shouldn't have been.

Jimmy pulled a slightly confused face. And since he obviously hadn't figured it out, he was entitled to his confusion. "One bullet…" he breathed thoughtfully.

It wasn't a question. I said, "Well, that's the bet anyway. You want to scrub it?"

Jimmy shook his head and smiled. "Nope. You're on!" He sat back down, pulled a packet of Marlboro from his pocket and gazed at it wistfully. "D'you reckon he'd see the smoke?"

I stifled a sigh. "He'd see…"

A bead of sweat ran into the corner of my left eye and it stung like hell. Plus, I was desperate for a crap. We were both out of luck.

"What do they call you, Jimmy?" I asked, filling time again.

He looked at me. "Eh? Who?"

"Your buddies…what's your nickname?" I don't know how, when or why it had come about, but everyone seemed to have a nickname.

His expression cleared. "Oh…Well, it was Rancid back in the regiment. Some of the guys here call me Rambo…"

Give me a nickel for every mercenary soldier nicknamed Rambo, and I'd be richer by at least a dollar. I did not ask Jimmy how he had come by either nickname. Instead, I asked, "How long were you with your regiment?"

He sighed deeply. "Not long e-friggin'-nuff! Seven friggin' years!

It was amazing how many expletives he could inject into a two- or a three-syllable word. I said, "Seven years is a long time to make up your mind. Why'd you quit?"

He pulled a rueful face. "I didn't friggin' quit! I was P-eight. Can you believe it? P-friggin'-eight!"

P-8? My knowledge of British military terminology was never great, but I had heard somewhere that P-8 was a medical thing. I smiled. "Clapped up?"

Jimmy shook his head and looked sad. "Nah…that woulda been a friggin' privilege!" He shook his head again. "It was me friggin' back. What a sod, eh? A prize friggin' sod!"

Then I had it pinned. Translating fuck into frig was as far as he could go on my man-to-man suggestion. It was an understandable compromise. I nodded. Then I remembered where we were and why we were here. "Where is he now?"

Jimmy again removed his forage cap, heaved himself back up to peer out over the rock, head cocked to one side, left eye first. And slowly. He had certainly been trained well enough. "About thirty yards short of the upside-down steam roller. Christ! He's really taking his time about it! Doesn't he know we've been waiting here for two friggin' hours already!"

I looked up into the searing maw of the sun and wished I hadn't. A movement caught my eye. It was a spider out for a stroll. A damned great hairy thing with a million legs. It paused level with Jimmy's right boot and contemplated the studs as if it were really interested in the technology of military footwear. I gathered up a mouthful of spit. I missed the spider by a mile and it sidled off without a care in its world. What do spiders have to care about? The glob of spit sizzled on the hard-baked dirt.

"Twenty yards." Jimmy said softly.

I wondered idly what his reaction would have been if I'd told him about the spider. Some people can't stand the things. I wasn't overly keen on them myself.

A wild dog hooted somewhere out on the broiling pan. It sounded lost, but wouldn't be. Desert animals know exactly where they are and what they are doing there. I said, "Let him come…"

Jimmy lowered himself back down to the ground and took up where he had left off. "Missed the uniform, I suppose…" He shot me a self-conscious grin. "Vain bastard, am'n't I?" Sad again. "And the lads, o'course. Friggin' good bunch, they was…"

I recognised his expression as one I'd seen on my own face in mirrors.

"…A couple of 'em was right bastards, o' course. Can't odds that, can you? But they was a friggin' good bunch. They 'ad no right…" His voice trailed off and he was silent for a moment, staring blankly at the ground. Then he smiled. "Wanna hear something funny?"

I felt old. I nodded. It was always nice to hear something funny, and it might just take my mind off the fact that my bowels were on the extreme edge of rebellion.

Jimmy chuckled. "I thought I was pulling a friggin' good skive. I had this date, see…with this chick…"

That in itself was funny. Why, I wondered, had he felt it necessary to confirm the gender! He went on, "The company was due a bleedin' parade, for some friggin' brass-hat. So I reports sick. Told 'em me bleedin' back was killing me. Friggin' lie, o' course. Anyway, the M.O. rattles me off for an x-ray, 'n off I trots…" The smile wiped itself clean. "…Guess what…" He shook his head at the injustice of it all.

But we shared a grin. It was a good story. And it was very probably true. Despite everything Jimmy was, or was not, I didn't think he was the kind to lie about something that was obviously so important to him. Discounting, that was, Medical Officers and double-dated girls.

I said, "And you never felt it?"

He frowned. "Felt what?"

"A pain in your back!"

"Oh!" he said, "Nah. There wasn't none. Not a single friggin' twinge! I only felt it at all when the bleedin' M.O. pokes his finger where it shoulda been hurting!" He shook his head again. "Must'a done it playing rugby or something…" He glanced down at me, a puzzled look on his face. "You'd think I'd've felt something before that, though, wouldn't you? Some clue…"

"You'd think," I agreed "But it'll teach you not to skive off. Right?"

He nodded glumly. "Yeah. So the bastards pensioned me off! Twenty-five friggin' quid a week, f'r Christ's sake! Who can live on twenty-five friggin' quid a week. I ask ya! Didn’t even keep me in beer!" He sighed hugely. "Anyway, that's why I'm here. Three-hundred and fifty quid beats the shit out've a lousy twenty-friggin'-five!" He looked suddenly panic-stricken. "You won't tell no bastard, will ya! About me back, I mean. Curly, nor no-one!"

Curly was B-Company's adjutant, and Chang's link to the recruiters. I shook my head. "Your secret is safe with me, Jimmy." And it was. Not that it would have mattered one way or the other. I didn't bother to ask him why he hadn't looked for a civilian job. Because I would have had to ask myself that same question. But then, I was on the beach for a matter of days only before my phone rang. My fall from military grace had been well publicised.

An animal of some sort appeared momentarily on the brow of the escarpment above us. Then it was gone. Jimmy also caught the movement. He squinted upwards.

"What was that?"

I said, "An animal of some sort. Check the gook."

Jimmy, tiredly, said, "Oh, shit!" and he raised himself up. He stared out for a moment, then he nodded. "Pass us me friggin' rifle. Bastard's nearly there…and not before friggin' time!"

The M-16A4 - the fourth generation of the M16 service rifle - is a good weapon. Not the best, not nowadays, but good. It's not really a sniper's weapon but, fitted with a telescopic sight - and this one was - it's quite good enough. It certainly was when you consider how many ways there are to kill people. Jimmy's gun had "ANDY" burned into its stock, alongside half a dozen notches. What goes around, comes around.

Andy had been a card, too. In his own way. Kamerhi had tied him to a tree and slit his stomach open with a bayonet. He'd then proceeded to shove handfuls of mud into the gash. I don't like to remember things like that, but, sometimes, the memories just seem to crowd in, one atop the other.

Powerless to do anything about it, I had watched Andy die from a hill overlooking the village. Irvine Patch - self-appointed "The Admiral" - had commanded that raiding party. Patch, like me, was an American. Not that I have the first clue what that observation means to the price of tuna. Patch hailed from Toledo, Ohio, and several lifetimes ago we had served together under the same flag, in Grenada and other places. Andy came from Tulsa, Oklahoma, and I'm from Minton, Nebraska. So what!

Jimmy was from Portsmouth, England. And Thomas Kamerhi, the guy in imminent danger of being shot anywhere but his heart, came from God alone knew where. And a hundred years from now we're all going to be history, meaningless.

If we weren't meaningless already.

I'm not going to say that Andy wouldn't have hurt a fly; his rifle had six notches on it. But I am going to say that he did not deserve to die like that. No-one did, does, or ever will do. But such is the coin of mercenary warfare. Which sentiment put me in the wrong business entirely. It's been said that if you can't take a joke, you shouldn't join. Well, I joined. Once thing was certain however; if I'd known how to do anything else, I would have been doing it. But I didn't. The world had taught me how to fight, it had not bothered to teach me how not to fight! Not that I had ever asked it to.

Jimmy hissed, "He's going left now. Shall I take him?"

I looked down at my grubby hands. My fingernails were topped with black half-moons of grime. Somehow they, and my legs and my body, seemed detached from my brain. It was as if I was sitting behind the observation window in some huge robot, an automaton. Push a button and a finger moves. It was a very strange feeling.

I lifted my own weapon from the ground and pushed myself up. The sweat ran in rivers down my face. I smelt, and badly. And if I didn't take a crap soon it would be too late anyway. I wouldn't have given a damn.

Kamerhi had started to move downstream, just short of the upside-down steam roller. He shimmered in the heat haze. Everything shimmered in the heat haze! It rose in tangible waves from the suffering earth like steam from a boiling pot. I thumbed off the safety and laid my gun carefully on the rock, which, I noticed for the first time, had a seam of purple ore running diagonally through it. I wondered what it might be.

I calculated the windage and elevation in my mind. But there was no wind, just elevation. For me it would have been a target shoot. And if Kamerhi had not been wearing a flak helmet I could have done the job leaving no more than a neat hole in his forehead. I said, "If he moves twenty yards closer, you take him…" I added, "One shot, remember!"

A joke, a seam of ore, an animal or a spider. Normal things, taken at face value. In a place like the DDR - Democratic Republic of Congo, a joke or a bet were as good a motivation for killing a man as any. Seams of ore were better, of course. The animals and spiders were the audience. But we - me and Jimmy - were not doing what we were doing for a joke, or seams of ore; not directly, anyway. We were doing what we were doing because someone of higher rank had told us to do it, and was paying us a bonus for the privilege. End of story. Almost! This was Iraq all over again. Or Yugoslavia. Only three things ever changed; language, clothes and weather.

Jimmy squinted along his sights and did not look so sure anymore. His face was covered with globules of sweat and I was reminded of a billboard advertisement for melons. He hissed, "Who is this bastard anyway?"

I said, "Just a gook." This was the need-to-know principle at work. Kamerhi was the target, and that was all Jimmy needed to know. Besides, it was safer, for Jimmy, if he didn't know. I mean really didn't know. Unless, of course, I had him pegged all wrong. Not that I knew it all. Nevertheless, what I didn't know I could take a guess at. Kamerhi was here to meet someone. And Chang, for reasons that he had kept to himself, had not wanted that meeting to take place. The guess would be who he was here to meet. But I didn't give a damn about that one way or the other. My hook had been Kamerhi himself. If anyone else were the target I wouldn't have put myself out. Which made it all the stranger that I was disposed to pass the killing shot over to Jimmy. Heat fatigue, I guess. Or pure, bloody-minded sloth.

Jimmy lifted his face from the rifle and looked at me. "You call them all "gooks", don't you…" Pure statement.

I supposed I did. A hang-over from South East Asia, I guessed. But enemies are the same the world over; as is the game we played. Either you're a hero when you kill them, or you're a murderer. I found it very hard to work out the moral distinction. And it was just as well that I didn't think I had to. Generally, in my own experience anyway, the U.N. took care of the morals issues. And the U.N only had morals when it pleased them. Like allowing several hundred Bosnian civilians to be massacred; men, women and children, when I was on the spot with a platoon of thirty well armed men, and could easily have stopped it. And I do mean easily. Pull back, they'd said. It's their fight.

Jesus! There was no fight involved! It was a one-sided feral bloodbath.

Jimmy placed his right cheek back on the M16. "You been in this line of work a long time?"

A good question. I grunted. "Since I was three."

He smiled understandingly. "Yeah…I know what you mean…" He chuckled. "Gets in your blood, right?"

That, I thought, was either another good question, or a sad but true statement of fact. When I didn't reply, Jimmy said, "I don't like killing bastards what don't know it's coming, though…not really."

Was that relevant? I didn't know. I had a feeling that from a victim's point of view it was the better option. Andy had spent some hours knowing he was going to die. So had those poor sods in Bosnia. I shook myself mentally. "Well, if you don't kill this one, and with one shot, it's costing you beers…you settled and ready?"

"I am that, boss…" Jimmy breathed.

Boss! This was a small improvement.

Jimmy lifted his hand from the trigger and stroked Andy's gun lovingly. To it, he whispered, "Don't let me down, you little beauty…"

Kamerhi , looking for a shallower spot to cross the river, turned again towards us. His face was nothing more than a dark smudge beneath his helmet, but I knew his features well. The ice-blue eyes and the wide jaw. And that ridiculous hairline moustache. Our paths had crossed several times; usually over gunsights. But here I was merely a spectator. Just looking.

Jimmy took his aim.

Africa, in its current frenzy of slaughter, took its aim.

I looked down at the dirt on the other side of the rock. There was a horde of ants down there. Red ones. Ants fascinate me. They're always rushing about, carrying stuff. And there are always twin lines of them. One going, one coming. Ants must live very ordered lives. I wondered, though, if they ever paused to pass the time of day with each other. Did they argue? Did they have aspirations? I also wondered how much you would have to pay an ant for it to kill one of its fellows. Or, perhaps closer to the point, how much you would have to pay an ant to turn a blind eye when the killing was going on.

The Nelson syndrome.

Heroic.

Except that I saw nothing heroic in General Claude-bloody-Mansfield's version of the Nelson syndrome when we'd returned from that sortie in Bosnia. He'd even smiled! None of our business, old chap! Just let them get on with it… The mental images of them getting on with it were still eating at me like a cancer. So I hit him. Very hard. Blinding him in his very British left eye.

Fists across the ocean, and all that.

So they'd crucified me.

And you don't get any kind of a pension with a Dishonorable Discharge.

CRACK!

The echoes of Jimmy's shot bounced back at us as a diminishing volley. The scrubland on the far side of the river came alive with the yelp and scream of disturbed wildlife. It didn't seem to bother the ants, though. They were either deaf, or in the pay of the U.N.

"Shit, shit, shit!" Jimmy spat, back-handing the sweat from his eyes, leaving a dirt-red smear across his face.

I had to concentrate hard to drag my brain back from wherever it had been. His shot had kicked up dirt some yards behind Kamerhi. His line had been fairly good, considering the range. Kamerhi was running; ducking and weaving.

I lifted my gun, ready to take over should Jimmy fail on his second attempt. I said, "Try again…Catch him on the zig."

Kamerhi was zigzagging towards a clump of bushes on the river bank, crouched low. The reflection of the sun exploded as one of his feet touched water. Like a firework. And for that instant the river was a beautiful thing. Jimmy sucked in a breath and let it out slowly through pursed lips.

CRACK!

Kamerhi went over in a cloud of dust.

Jimmy straightened and waved the rifle in the air and yelled, "Friggin' ding dongs! I got the bastard!"

I nodded. Sadly, it didn't seem an important event. I felt none of the satisfaction I had been looking forward to. "Yeah…"

Jimmy said, "What now?"

His face was the Sioux Falls and this time I was reminded of the "Happiness is…" series of cartoons. I studied the fallen man. He wasn't even twitching. But that didn't mean too much. Men have lived for some time with a bullet lodged deep in their heart. That was the extreme outside edge of possibility, of course, but it was not impossible. I lifted my rifle and put a shot into his hip; his torso was behind a rock. A bluffer can't lie still when he's shot in the hip. Apart from the slight jerk as my bullet hit home, he still did not move. Silently, I said, well, that one was for Andy.

So, part one achieved.

Which was all well and good. But part two was to have been the photograph. The big problem was that Jimmy had lost Chang's camera. I Hmm'd a thoughtful Hmm.

"Well…" I said tentatively, "There's the photograph."

Jimmy looked at me sharply, his eyebrows knitted again. "I couldn't help that!"

Which was true enough. We were crossing the Tagula River and it was in flood. The pack was ripped from Jimmy's back. I couldn't come over all holier-than-thou because the provisions pack was ripped from my own back in the same way, along with my mobile phone, which had a neat camera facility built into it. The resolution wasn't that hot, but it would have sufficed. Staying alive was prime back at that crossing. As I said, I should really have thought it through. But I hadn't bothered.

However, there was an answer.

I wondered whether I ought to do what had to be done in the absence of a camera. Jimmy was keen, to be sure, but I had a feeling that, tainted or not, he was still a human being, down there under the tough-guy façade. Which was probably another reason why I was warming to him.

But then, I reasoned, the camera had been in Jimmy's charge. A pedantic point, I realise, but valid none-the-less. And I was tired right through to my bones; almost too tired to be bothered to take the dump I so desperately needed. I slid my bayonet from its sheath and placed it in Jimmy's free hand. I said, "Chang needs a photograph. For proof. Remember? Don't come back without it, he said. Chew on that while I take a crap…" We were not in a desperate rush.

Jimmy looked at me, then at the bayonet, its oiled blade glinting in the sunlight, then back at me. I looked at Jimmy, keeping my expression neutral. "There has to be a photograph, Jimmy. The whole damned deal is useless without it…" I reminded him. Proof, it was all about proof. No-one took anyone's word on anything in our business. I added, "Or, since we can't give him a photograph…" I let that hang in the suffering air.

Jimmy's face blanched suddenly. "Oh, Jesus fucking Christ!" he breathed.

"Right…" I agreed. I felt ancient, decrepit, washed out and sick of the whole bloody mess. I was experiencing those kinds of feelings more and more these days. Maybe I ought to take a correspondence course in something or other. Get a new skill.

Jimmy looked terrified. "But - but…" he spluttered.

I waited to see what he had to say. I really felt for him.

"We just tell 'em that we got him…they're bound to believe you!"

And pigs, I thought, are aerodynamically blessed. I raised an eyebrow and looked at him.

"I know!" he said briskly, changing tack." I'll carry the bastard back. That'll be even better, won't it?!" He was pleading with me.

I did give that some thought. "You'll carry a dead man back fifty miles…is that what you're saying? Back over the Tagula rapids? And through that bloody swamp?" I loosened my belt and dragged my trousers down. I couldn't hold it any longer.

Jimmy had his mind on other things. The sight of a ranking officer crapping on the ground would have seemed commonplace to him at that moment. "I can do it!" he nodded emphatically. "Jesus Henry, he can't weigh that much!"

I crouched there and crapped, and felt instantly better. I did not feel like arguing, but it's amazing how much a dead man can weigh. I nodded down at the river. "Go ahead…if you reckon you can." I was wishing that he could, but I knew he couldn't. Even with two of us doing the carrying it would have been a non-starter.

Jimmy offered me the bayonet. He looked decidedly relieved. For our own reasons, we were both relieved. I shook my head. "Take it with you…You never know." I smiled up at him and added, "And mind how you go with your back…Chang doesn't go in for sick parades."

Jimmy stepped around the rock. I finished my crap then waddled around like R2-D2 looking for handfuls of grass to wipe my arse with. But that was one barren mountain. In the end I didn't bother with sanitation. I doubted I could smell any worse, in any case.

Jimmy did try, I'll give him that. I watched from the rock as he tried to get Kamerhi up onto his shoulder. Five times he tried, and five times he failed. I guessed he was giving away at least twenty pounds. Possibly a whole lot more. I saw the white blob as he glanced up at me over the water. At any other time, under any other circumstances, it might have been hilarious. But it was not hilarious, not even slightly. It did not even rate a smile.

Then Jimmy tried dragging the body. But that was not on either. I looked down at the ants. It may have been my imagination but they seemed to be moving more urgently now; concentrating harder on the task at hand; studiously disregarding the strange happenings around them. Which, I thought, was ironic. That is exactly what I was doing with regard to the bigger picture. Ignoring that thought, I craned forward to get a better look at the ants. Both columns disappeared down, and emerged from, a hole under a big stone. One of them was carrying something at least five times its own size. I was reminded of Jimmy, but did not look back over the river.

I heard Jimmy throwing up.

I looked over my shoulder and saw the spider. It ambled over my way. I said, "Oh, Hi, spider..."

The spider looked me up and down and did not seem impressed, for which judgment I could not fault it. It wandered off again.

I heard Jimmy throwing up again.

I pushed a button inside my head and a hand came up and waved a cheery goodbye to the spider.

Murphy's Cafe and Bar was neither of those things. It was a brick-built, tin-roofed hut on the slope leading from the compound to the village of Bhami, just over a mile away. The hut had begun life as an air-conditioned off-base ammunition storage unit which hadn't filled the need. The ammo store had been moved into the compound and the hut left empty, until someone - I don't know who - had suggested "Murphy's". It was big enough and it had windows and a generator-fed electricity supply. More importantly, for Rest and Relaxation purposes, it was outside the compound. Getting out of the "office" once in a while has beneficial effects on a person. Good business practice. An effective loss leader.

"Downtown" Bhami was a cluster of mangy buildings and mud-huts that the river should have washed away years ago. The river was the main highway; the road being little more than a dirt track. And for sixty miles in any direction, using the compound as your pivot, there was very little but jungle. A single telephone line constituted the only hard connection to the outside world. It wended its way north from Fariale, was spurred into the compound and the mission, before snaking on up to Mumbgwallo. The latter could rarely be raised because Patch's deep-incursion patrols seemed to use the line for target practice. All very annoying.

On the southern perimeter of the village, snugged in a bend in the river, was a clearing. That was the airfield for any fixed-wing traffic we might have; but it was an airfield only loosely. The runway was a tightly-woven hard rubber matting laid on the grass. You couldn't actually see it because the grass had won the battle long ago. But it was there. The control tower was a corrugated iron hut that had never seen a paint brush and was, consequently, almost eaten away with rust. There was also a windsock of sorts. A man trying to reach that field from, say, New York, would have a job on his hands. The first five thousand miles would be easy enough. The last hundred would be nigh-on impossible. He would have to use the river which, approaching from the western hemisphere, would be an against-the-flow trip and would take forever if not longer, or the dirt track which, dependent upon the vagaries of the weather, may or may not be there. Or he would have to use a smallish fixed-wing aircraft, provided he could find a pilot stupid enough to attempt that impossible flight. Or he would have to utilise B-Company's helicopter. He could only use the latter if he had taken Curly's shilling.

Also downtown was a general store and a mission church. There was also, strangely, a shop where a man would mend your shoes. The rest of the local populace, dirt farmers and Hema tribespeople to a man, were scattered in the hills surrounding the village. The mission church, one of a bare handful of brick-built structures, had been there for a very long time indeed, whilst Murphy's and - I think - the store, were only as old as the B-Company compound. I don't know the story of the guy who mended shoes. But we used his services quite a lot.

The man who ran Murphy's was as black as night, and why he called himself Murphy was another mystery. Maybe he didn't. Maybe the name had been someone else's idea. The bar may have been his own, or it may have been some kind of a franchise, subsidised by Chang. I really did not know, and was not desperately interested. It was there to be used when there was nothing scheduled in the compound, and that was it. The man who ran the mission church was an aged German who had a daughter. God alone knew what religion the old German attempted to purvey, or how he - they- had ended up out there on the extreme periphery of insignificance. Everyone, with the possible exception of her old man, knew what the daughter was purveying; certainly since the compound had been here. What she did with herself before the sudden influx of some two hundred randy mercenaries didn't bear thinking about.

Murphy said, "I got whisky. Double malt…" He was squinting at the label as if that was the first time he'd seen it. "You want it?"

It was all bizarre. Like some movie of a western ghost town. Except that this was in the middle of Africa and the population was mostly Bantu-speaking natives. Murphy, for example, wore threadbare western clothes when he was serving, but reverted to African thobe when he was on his own time. He was always unshaven, but the stubble never seemed to thicken. I think Curly, or, more probably, Chang, had brought him in from some other place when Murphy's had become an entity. The village, such as it was, just happened to be here. Whatever the truth of it all, it had elements of a miniscule, reality-mangled garrison town that, with the possible exception of the church and the few houses around it, would not have existed without the garrison. Certainly it would never have been affected by progress and the changing centuries. There were no communications satellites in the skies over Bhami, or any place near it. It was a dead zone that the outside world seemed happy to ignore.

Chang kept a hefty generator going 24/7. The cables supplying power to the ammo store a/c unit, luckily, had not been removed, and now powered Murphy's refrigerator and a few light bulbs. The actual air-conditioning unit had long since given up the ghost. I doubted that Murphy's Café and Bar was a magnanimous gesture on Chang's part. He was, significantly, an ardent teetotaller, but was astute enough to realise the necessity of keeping his men as cheery as possible, given where we were and why we were there. Morale, in any army, is an important factor. We were not an army, but we were the next best thing. This evening, the only customers as yet were Curly and myself. I was drinking beer. Curly, his sharp features accentuated by the harsh shadows thrown by a single bare bulb in the ceiling, was currently empty-handed.

Curly said, "I'll take a shot, Murph. But if you've watered it down I'll cut your balls off!"

Under any other circumstances that would not have been a joke. If Curly said he would cut your balls off, that's exactly what he would do. But I wondered why he thought a man like Murphy would know anything at all about watering whisky down, let alone why someone might do such a thing. There were optics on the wall behind the bar, but Murphy always looked confused when he used them. The till was one of those old fashioned monstrosities that required some button punching and a lever-pull. I had rarely seen Murphy use the damned thing. We all paid for what we drank, but it was probably only a paper exercise. All part of the façade.

It was six-thirty in the evening and, outside, the sky was a canopy of deep pink. The humidity level was, for once, at a fairly comfortable level. It would get worse as the night wore on.

Curly took a swig of the drink and grimaced with pleasure, his cold eyes flashing. He said, "Wonders will never cease!"

I sighed. "I think you're wrong…"

Curly frowned minutely, as if wondering what I meant, then his face cleared. "Oh, here…" He dipped into a pocket of his camouflage fatigue uniform and pulled out a wad of dollar bills. Fifties. He went on, "Chang was very pleased with your little effort, chum. There's a bonus in here for you."

Chang was the Commanding Officer of B-Company. Chinese. And he liked to run a taut, professional outfit. From the day-to-day administration of a garrison out in the middle of nowhere at all, right down to keeping Murphy's on a business-like basis. To his dubious credit, he certainly managed all that. He rarely ventured outside the compound. I don't know why. He was also the go-between; dealing with Joshua Mtomo -the Pretender to the throne of the U.P.C.(Union des Patriotes Congolais), and the rest of The World at large. Mtomo was the man with the money and high aspirations; The World was what he hoped to conquer. In there, too, was a man called Robert Urundi, who liked to think that the country was actually his. Irvine Patch was under contract to Urundi, and had been for some time before I signed with Chang. Chang was under contract to Mtomo. Overall, it was a confusing picture. But that confusion was none of my business, and even less of my concern. I had learned that very hard lesson some time ago.

Status Quo.

Africa.

Or wherever.

I said, "Oh…" and pocketed the wad of notes. Back at the compound I had a tin box full of dollar bills. In terms of cash and collateral, I was a rich man. I did not feel rich. All very strange. I did not think I was the archetypal mercenary - if such an animal actually existed. I once thought I could be one, however, that's for certain.

Curly said, "How did Jimmy make out?"

In my mind I heard Jimmy throwing up. I said, "Jimmy took the photograph."

Curly laughed. "Yeah! In three-bloody-D! Chang was tickled pink. He says he might have it shrunk and made into an ornament."

There was no joke intended there, either.

I said nothing. I had known Curly for some two years and had still not really made up my mind about him, one way or the other. Remembering that we were a mercenary unit only loosely attached to the UPC, he seemed just what the job demanded.

He said, "Chang says Patch is encroaching up north again, digging in someplace apparently. If that's right, d'you want another crack at him?"

As the company adjutant, that was one of his functions; passing on the day-to-day assignments. I said, "A job?"

Curly frowned. "It'll be a mission!"

There was a difference. Missions were required under the terms of employment. Jobs were over and above the call of duty, and paid extra. The Kamerhi photograph thing with Jimmy had been a job.

I thought about it. There's no denying that mention of Patch's name did up my pulse rate a bit, as it usually did. But before I could respond the door flew open and a group of company guys clattered in. They looked like the recent intake. "Cherries", they were called in 'Nam; "squaddies", if you're British. Untried newcomers who had yet to grow into the new uniforms they wore. A couple of them were already drunk. They pulled their horns in a little when they saw Curly; but not by much. I guessed they were assigned to Jose Santana's platoon; he had the current short straw on training details. And these men would be at a loose end, because Santana was off somewhere on another of Curly's "jobs" They sat themselves at one of the two tables and started to sing and generally horse about. Murphy, all smiles that weren't smiles, went over to take their orders. The air of sham was tangible, at least it was for me. A bar in the middle of nowhere that wasn't actually a bar. A barman who wasn't a barman. A garrison town that didn't even know it was one. A local population that was as puzzled as a population could ever be. It was all too ridiculous. On the other hand, it was the only reality we had, and I was part of it.

Curly raised his eyebrows and shook his head. "Let's grab a bollard outside…" There were a couple of stools out there. One of the men yelled over. "Hey, Curly, Hanson, here, wants to know if we can borrow the chopper." Full of false bravado. I cringed inside. They would soon learn the dangers of calling Curly by his nickname. To the company at large he was "Number-Two" or "sir", or even Captain Parsons. I think his first name was Hugh, or something like that.

Curly touched my arm and led the way to the door. "What the hell d'you want the chopper for, Carter?” he said over his shoulder, “there's no place to go…" Curly let the man down lightly, but would have filed the event away for future brutal exploitation. Curly was very particular about who did and who did not call him by his nickname.

I didn't hear the response because I wasn't listening, but I was mildly impressed that Curly seemed to know the man's name. I had problems in that direction. Faces, I was okay with, but names, aside from the guys in my own platoon and a few others, never seemed to stick. I stepped outside into the stale air. The darkening sky was beautiful, but the beauty ended there. Down here it was seedy and unfinished. The pervading smell was of rotting vegetation and rancid mud.

Curly stepped out behind me and we sat on the stools. "What about it?" he asked. "You interested?" He unslung his M16, reached around and propped it against the wall. If he'd seen anyone else do that he would have dropped on them like a ton of bricks. It was standard practice - mandatory, in fact - to keep your weapon actually shoulder-slung at all times, especially outside the compound.

"Sure…If it's a mission." There was actually a clue in there. He was asking me if I wanted to accept a mission, when missions were there to be carried out whether you wanted them or not. They seemed to be walking lightly around me. As if they didn't want to push me too hard. I should have been giving that observation the weight it deserved. I said, "What've you done with Baker section, Curly? B-spider's empty." Baker was my section, and B-spider was where they lived.

Curly lifted his hands. "Don't fret, they're safe."

I nodded. "Safe where, Curly?"

Curly looked vaguely uncomfortable. "I didn't know how long you were going to be out, Marty. And they were sitting around…"

I didn't doubt that. Baker section was notorious for sitting around when there was nothing specific going down. I said, "Relax, Curly. I'm just asking where they are."

"Fariale…" Curly said, an unmistakeably apologetic edge to his voice.. "An ammo pickup…" With a shrug, he added, " A walk in the park."

I wondered why he might think I'd be angry about that. I said, "Fine. But that's a five-day round-trip." Fariale was the entry point for ordnance shipped in from various arms dealers around the world. Mtomo himself took care of that aspect.

Curly smiled an uncomfortable smile. "Yeah…Gives you some time off, though, right?" He dashed on, "So I'll set it up. Maybe a week, if it all comes together…Oh, and Mtomo's coming up the line tonight. Chang says he wants a parade. First thing. Oh-six-hundred."

A parade! Jesus! They were still trying to make out that B-Company was some kind of a real military regiment, when, in truth, we were just a few hundred guys on the make! A mercenary unit. We had UPC uniforms, to be sure, with impressive badges - fancy-dress, almost. Probably designed by Mtomo. But most of us preferred to wear standard jungle camouflage fatigues. We also had some fairly efficient weaponry. The helicopter, a dozen or so trucks of various tonnage, jeeps and a couple of half-tracks. Plus some useful electronic stuff. Hard currency can buy almost anything. An exception, in our case, was flak jackets and bullet-proof vests. For some reason these items were not currently available on the world arms market. Boots, also, seemed in short supply. Other than these shortfalls we were fairly well equipped. Even so, we constituted a very dubious regiment!

A-Company was over to the west at Bunia, but they were Hema irregulars supported and outfitted by Rwanda. And C-Company, fostered by Uganda, was stationed way up north in the Great Lakes region, protecting Mumbgwallo airport. C-Company also used mercenaries. But these men were so-called Askaris. Home-grown black African mercenaries. "Foreign Volunteers", the press called them. B-Company, us, was on the books as a Paramilitary unit. For Paramilitary read Mercenary. We also had Askaris on strength. But not many and not often. What no-one knew, was whose pen actually wrote in the books! Speak to a Joshua Mtomo supporter and they'd tell you that Robert Urundi was the rebel. Speak to a Robert Urundi supporter and you'd hear the opposite. Speak to a local who was simply trying to live day to day, and he or she wouldn't know what the hell you were talking about. Simple existence was their only concern. The African Story.

I said, "Well, if it makes him happy, give him one." At the very least, I thought, I would not have to listen to Baker-section gripe about making having to make themselves look presentable for something like that.

Curly stared into his drink. "Not quite your style, is it, eh?"

I said, "I don't have a style…" To myself, I added, not any more!

Curly went on, "Tell me about it!" He grimaced. "But it aint like Afghanistan, is it"

I grunted. "I wasn't in Afghanistan."

"Oh, yeah…" said Curly in a new tone of voice." It was Iraq, right?"

I didn't answer. Curly knew all he needed to know about me, and what he didn't know, he could whistle for. Chang, on the other hand, knew just about all there was to know about me and my history. It was his business to know those things. And it was his business how much of that information he passed around, even to his 2i/c.

The noise from inside the bar swelled suddenly, and there was the sound of breaking glass.

Curly clucked his tongue and raised his eyes to the heavens. "Bunch of no-hopers!"

I said, "Your guys hired them, Curly."

He pulled a face. "Yeah. But you gotta take what you can get these days…" He drained his glass. "There aren't many old "dogs" like yourself to choose from." He looked at me and shook his head. "I never figured out why you took my shilling…"

Curly used that term a lot, as if he was proud of it. It was a while before I'd had it pegged. He went on, "You could have hired on with Patch's mob. You could've been up there with them, not going on missions against them."

He wasn't telling me, he was reminding me. All that was stale news. I sipped my beer and said nothing. I had accepted Curly's commission because it was the lesser of several evils, and for no other reason. Even before my discharge from the Marines, five years before, it had been common knowledge that this part of the world in general, and the Congo in particular, was the re-emerging Mecca for mercenaries, just as it had been back in the sixties. Hell, the recruiters were hovering at the gates of every military garrison in every corner of the world, and regular army guys were defecting to the money all the time. Patch did just that. So, when circumstance had pushed me onto the market, my antennae had been up and active. When the calls came in, as I guessed they would, I was ready for them. All except one.

Curly went on, "Now, they've got a real organisation going for them! Good loot. The best equipment…" He pulled an impressed face at me. "…We've seen some of it, right?. And real fucking officers! Not like our chinky friend…"

I said, "None of it is real, Curly…" I wondered why he was denigrating Chang. He had never hinted at that line of thinking before; certainly not in my hearing. I wondered why he was doing it now. Besides, Chang, a professional soldier to his bootstraps, seemed to be the ideal candidate. I was aware of the warning bells tinkling in the back of my mind. I had heard them before, and ignored them. What everyone else did was their business. But, for sure, someone out there was doing something. Kamerhi was supposed to have been meeting someone on our side of the fence. Could that person have been Curly? I discounted that thought the instant it arrived. Had that been the case Curly would surely have gotten some kind of a warning to him.

All the same…

There are always problems in units of any size. Barrack room lawyers, and the like. Undercurrents, rumour, gripes. Even plain, common or garden gossip. In regular service I had learned, if not to ignore it, then to accept it with the proverbial grain of salt. In a mercenary unit, however, the ramifications of these things can be far more dangerous. Money talks an entirely different language, provoking wildly diverse bedfellows. I decided to listen to the bells in future. But not today. I needed the mental break.

Curly just looked at me blankly. Then, a shade weakly, he said," Maybe not...maybe not…" He drained his glass. "Another?" He indicated my empty glass.

I handed it to him. "Go on, then…" He disappeared back into the bar and the ruckus dimmed momentarily. I wiped my mind clean of the bells and just sat there, thinking nothing. That was the paramount way to while away secluded moments. Think nothing, calculate nothing, decide nothing. I doubted it was working, of course. But it seemed worth trying. Curly was back inside a minute. He handed me the glass and eased himself onto the stool, carrying on as if the last part of the dialogue had not ended on a negative note.

"Why in the hell did you tie in with us? Really! Why did you choose Chang over the Admiral? I'd like to know."

I didn't doubt it. I thought, the bells, the bells!

It would be a valid point from Curly's point of view, however, if definitely not from mine. Patch had been the first on the scene. He'd resigned his commission in favour of Urundi and his money about a year before my brush with Mansfield, and we had kept some kind of an intermittent dialogue going. The occasional e-mail and such. Plus a couple of meetings when we both happened to be in the same country at the same time. I heard all about his new life and the fortunes he was managing to salt away. On the face of it, it had seemed promising, if not tempting. And I was hard-pressed to fend off his requests for me to join him. But it wasn't for me. I was still trying to impress my father, a career-Marine all his working life.

But during our last pub crawl - in Berlin, I think it was - Patch seemed to have changed beyond all recognition. As if a switch had been thrown. While we were never close enough to have been called brothers, we could at least share mutual time off with a good degree of fun. Suddenly, it seemed, he was a different person. Edgy, moody, and too quick to anger. His eyes, like those of a confirmed drug addict, were never still. It was as if he were constantly on the lookout for danger signs. And with a few drinks inside him he became almost manic; viciously so, picking fights with random guys who dared glance in his direction.

He had promoted himself Admiral, he told me. He had once been a S.E.A.L. so the nautical flavour of that rank was not so far out there. What was out there, well beyond my comprehension, was that he chose any kind of rank at all. There were unmistakable signs of "General" Idi Amin about him. Something had turned him.

His stories, too, were the stuff nightmares are made off. Where we used to swap filthy jokes, now I was listening to stories of unrestricted rape, cruelty for its own sake, and open-season murder. It's well known that power is a corrupting influence. Here in Africa, commanding Urundi's forces, he appeared to have all the power in the world. And he was revelling in it, waving it in front of my face like some kind of a recruiting flag. The power to arbitrarily determine life or death, he bragged, was staggering. Like a drug. And the residue of that drug was there to be seen in his eyes, his movement, his voice. In everything he did. It struck me in Berlin that he was experiencing a kind of withdrawal symptom by not being where his power lay; having to live by rules which were not of his own making. He was the classic fish out of water.

What really sickened me was that he actually seemed to think that that power would impress me. Worse, that it would interest me. He was arbitrarily tarring me with his own brush, and that grated more than anything. To say that he was no longer a comfortable man to spend time with would be an understatement. I simply did not know who I was talking to anymore. And I was glad to get away.

Then came Bosnia, and my brush with Mansfield.

My father died shortly after my D.D., a bitterly disappointed man. I had tried to tell him the way it was, but he was not listening.

And Patch contacted me again. He had heard the news, so why didn't I join him? He would engineer me a commission as his 2i/c. The good times would roll again! Stupidly, I lied through my teeth, and I don't know why. Old time's sake, maybe. He was just too late, I told him. Dammit! I had already signed up with another agency. I really should have told him the truth; that nothing could induce me to work alongside the man he had become. It was not hatred, it was revulsion. Just as my father was probably revolted at what he thought I had become. My rationalisation was that, short of half-blinding a high-ranking British officer in what I considered to be a damned good cause, I had not actually chosen the way my life had turned out. Patch had done just that, and then some!. It's a pathetically weak argument, I realise that, but I have no other. But that lie, and incidents that followed, set the seal on the way things eventually turned out.

I did some work for Brierson Global Arms (B.G.A.inc.), in Chile, plus some police work for the Chilean government. That was okay. As were a few stints here in Africa for various mercenary outfits, mostly down south in Zimbabwe; another country that didn't know its arse from its elbow. Then there was some advisory stuff for an off-beat film company in Australia. That bored me witless. When Curly's recruiters eventually appeared at my door I was more than ready to accept another front-line commission. Despite that, or, more probably because, Patch was the opposition.

Patch, naturally enough, got to hear about it, and I had one last e-mail from him. This is going to be a blast, he said. Between us we could end up owning the whole bloody country! He had misread me utterly. But the fault was mine. I should have shamed the devil and owned up to the truth.

And so it had begun.

For two years we had played the game out, with Patch thinking that only some unwritten mercenary code – a Pagan-like oath - was keeping me on the opposite side of the fence.

The most telling incident happened last year.

It was the only time - since Berlin - that Patch and I had found ourselves within hailing distance of each other. And, unknowingly at first, we had actually exchanged bullets. It was a relatively insignificant skirmish up in Goomi territory. The important fact was that I found myself out of ammunition at just the wrong moment. I am not so sure that Patch was in the same bullet-less boat. But I hope so. We stood there, some fifty yards apart, with the fire fight happening around us. I do not know what was going through Patch's mind, and I'm not even certain what was going on in mine. But I do know that if I'd had a bullet up the spout, I would have used it on him. As far as Patch would have been aware, however, I was still able to fire my weapon. Stupidly, I aimed at his chest and mouthed "Bang!" He obviously took the fact that I didn't actually fire, to have another meaning entirely. We stood there for a few pulsating seconds. Then he shot me a beaming smile and lifted a salute.

Likewise, old buddy… Let's do lunch sometime!

And then it was over. He turned on his heel and was gone.

But my original instincts had been good, I was rock-bottom certain of that now.

For proof, there was Andy. And Clive Beecher. And Jeff Mack. Baldy. Stiff-lip-Sanderson. Those six gook girls up in the mountains. And, maybe most of all, that mangy old mutt down in Petersville.

Who but Patch could hang a dog with fuse wire?

I realised that Curly was saying something, but had not heard a word of it.

"Eh?"

Curly leant closer to me and lowered his voice. "I said, they're going to win in the end, y'know…"

I dragged my mind back and inwardly sighed. So he was part of it…whatever it was! Then again, that line of reasoning required a giant leap of faith. If Curly had practical communication with Patch, then why the hell hadn't he warned him that I was taking out his 2i/c? It was a puzzle. As a temporiser, I said, "It's never over…"

Curly smiled and sat back. "Until the fat lady etcetera etcetera…" He waved his glass in the air and whisky slopped everywhere. "But a clever man calculates his options, old buddy…"

In drink, Curly would frequently lapse mid-Atlantic. He was British, of course, like Jimmy. From the north of that country, apparently. Britain, I think, has more in-congruent accents than America, and that's saying something. Then he surprised me even more by saying, "I wish to Christ I had the chance to change sides…"

I couldn't even begin to fathom where this was headed. I looked at him and was confused. So I stopped looking at him and raised my eyes to the sky, which was darkening by the second. The pink had been replaced by deep crimson whilst, to the east, over the walls of the compound, it was a blue-black nothingness. The humidity level was rising by the moment.

Curly glanced back at the door to check we were not being overheard, and went on," But you could…I happen to know that Patch would still pay a lot for you, chum. He made Chang an offer. Chang turned him down. Told me not to tell you about it…" He chuckled, but the chuckle failed to reach his eyes. He added a conspiratorial,"…but I told you, eh?"

Don't delve, I told myself. Take it all at face value and figure it out later. It was certainly not unheard of for one mercenary leader to have contact with his opposite number, and on any level you might care to guess at. Business, as the old saying goes, is business. Up until the moment that actual bullets are exchanged, anything at all is, and always has been possible; deals, double deals, negotiation, even friendship. And strong friendships at that. Just like the friendship Patch thought we had going for us! But it all stops when your paymaster yells "Fire!" At that moment you use everything you ever learned about your "friend" to destroy him. At least, that's the implicit rule. It doesn't always work that way, of course. Sometimes you run out of bullets! I smiled. "You told me."

I'm not sure what reaction Curly was expecting from me, but, whatever it may have been, I obviously disappointed him, as I was disappointing myself. He allowed a slight frown to crease his forehead. "A real fucking army, they've got up there…" he hissed, "Jesus…I can almost taste it!"

He obviously wanted me to taste it, and I was having none of it. His frown deepened for a moment. Then he seemed to give up on whatever idea he had been harbouring. He sat back and raised his glass at nothing in particular. "Here's to Africa, right?"

"A great country," I said. "And it'll be a wonderful place when they hammer the last nail in." Jokes are always good therapy.

Curly said, "Amen to that!" He didn’t see it as a joke at all. We lapsed into an uncomfortable calm, embellished only by the drunken noises from inside the bar.

Up at the compound, the floodlights came to life, creating a magical halo above it. There was the sound of a group of men leaving the gates. They were invisible in the deep shadow below the glow of the floods, but they would be headed here. Time to go.

Curly placed his glass on the ground, grabbed his M16, stood up and stretched. "So Jimmy did okay," he said. His tone indicated that he had given up on his previous train of thought. Which suited me fine.

I nodded. "Jimmy did great." I did not tell Curly that Jimmy owed me beers.

Curly said, "Thank Christ for that. I think I'll bump him up a notch. Echo could use a two-striper. D'you think he'd appreciate a bit of power?"

Echo Section was Jamie Carlisle's bailiwick. I said, " Don't ask me…ask Jamie."

I was becoming a master of the obtuse.

Another of those looks seeped across Curly's taut features. I held up a pacifying hand and nodded. "Sure, Jimmy'll get a kick out of that."

Mtomo did not get his parade.

A couple of hours after Curly and I got back from Murphy's, Chang received a frantic call from Red-four - Nessie's Able-Section patrol - up in Shagland.

Shagland. It was actually a map reference, but some wag had added names to some of the references on the map; areas of special significance. The names had stuck. Shagland was a section of jungle right up in the Ntebbe hills, some fifty miles north of the compound as the crow flies. There were a few isolated settlements up there, and Patch had been trying to subvert them for a long time. Others had tried similar. First up there, in my time anyway, was a logging company. I don't have a clue what their business plan could have been, but they had actually tried to drive a road through to the place. Essentially, though, subversion had not been on the logging company's agenda, they simply needed the settlements and surrounding countryside to be devoid of inhabitation. In other words, they needed that area all to themselves, and sod the locals. Some four months ago they'd slunk off with their tail between their legs.

The populace up there, for some God-forsaken reason, supported Mtomo. This was just as well, because Shagland came under his jurisdiction. They had no time for Robert Urundi, Mtomo's opposite number. I think Patch lusted after that area because he knew something about the logging company's thwarted agenda that we didn't. It was a game of African Monopoly. And I was in jail waiting to throw a double.

Nessie - shortened from The Loch Ness Monster, a nickname without familiarity or even a vague hint of humour - was a Scot. Real name Andrew Bridges. He was a pug-ugly brute of a man. Well over six foot tall and big like a mountain. The thing about Nessie was that he spoke several languages, if with a heavy Scots accent. He'd been married to a French girl, living with her and her family for some years. He claimed to actually think in French. And he probably did, because, under pressure, he would revert to that language mechanically. This could have been a problem, because it was usually the pressure moments when orders had to be issued and acted upon very quickly indeed, so if you were in Nessie's platoon, and you didn't speak French, you were pretty much screwed. A compromise was reached. B-Company could boast a few actual Frenchmen, plus a handful of others who spoke the language well enough to be assigned to Nessie's platoon. It was a peculiar situation nonetheless. Right now he was in trouble with one of Patch's deep-incursion patrols and needed bailing out. But that was all we knew.

An ad hoc section was hastily thrown together - seventeen strong - with myself in command. This, simply, because I happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time when the call came in. Plus, of course, I was a platoon commander temporarily short of a platoon to command. In many ways I was glad. Certainly it was a legitimate reason to ignore the bells and concentrate on what I seemed to do best. The seventeen men were a mixed bunch and I only knew half of them by name. Ron Pearce, my own section 2i/c was amongst them. He had been in the sick bay with dysentery when Curly had commandeered Baker-section for the ammo run. And I only found that out by accident. Pearce, another ex-marine and a very competent soldier, insisted that he was well enough to come along, and had more or less begged me. So I had allowed it. I could not, however, have a questionably fit man as second in command for this deal. So I gave him a walkie-talkie and told him to make himself useful where he could. He was happy with that. And I was happy to have him along.

Normally, with a section out in the field, there would be a designated platoon on standby for just such a contingency. This night, for some reason, there wasn't. But there was no time for an inquest. Benson, the South African pilot, was roused from his sleep . We all grabbed weapons and some grenade belts and piled into the helicopter. At just past midnight we were airborne.

Thirty minutes later we were in position by dead-reckoning. The G.P.S. box was useless out here. I stared out the window at the black void beneath but could see no signs of a fire fight. I hit the transmit button of the shortwave radio. "Red Four!…Red Four!…Give me a code-two flare…I repeat: Code-two!"

Code-2, for this week, denoted a blue flare. Other colours had different numbers. This was to avoid being drawn into an ambush by someone listening in to the transmission. It was standard incursion practice. Not fool-proof, but workable. The radio crackled. "Code-two flare going up…" I could hear a crackle of small arms fire as a backdrop to the voice, which carried a very definite edge of something bordering on panic. I did not know whose voice it was, but I knew whose voice it wasn't! Then, a few seconds before the flare burst to life, I saw the flashes on the ground, some way off to our right. Then the flare blossomed. I yelled forward to the pilot. "See it?"

"Got it!" was the reply, and the deck heeled beneath our feet. I cast a quick eye over the men. They sat there in the feeble glow of the red night-vision bulbs, their eyes glinting like cat's eyes on a freeway. "Lock and load!" The sound of bolts and safety catches being worked was like a hatful of ball-bearings dropped on a tin roof. I smiled to myself and felt a sudden lift in my spirits. This was where it was all at. This was my reality and I was comfortable in it.

I went back to the walkie-talkie. "Where d'you need us, Red four?"

The voice came back. "Right there! Right where you are!..." A pause. Then, "The flare…see it? Right on top of it!" I suddenly recognised the voice. It was Raoul Pett, Nessie's comms number. Pett was a French/Moroccan who played poker with naked photos of his girlfriend when he was short of cash. I used to wonder if she knew what he did with them. I guess it was a toss up either way.

The blue flare had floated back to earth but was still smouldering.

Benson's voice came over the intercom. "I have it…going in!"

I slid back the cabin door and the noise of close gunfire burst in with the downdraft of the rotors. The adrenalin began pumping through my veins, as it always would at the prospect of immediate action. Benson put us right down on top of the dying flare and we fell out into the night. As the last of us hit the ground the aircraft, dragging a ribbon of tracer rounds with it, was already clawing its way back into the sky and out of harm's way. Benson would go back to the compound and await our call. In the strobe-like lighting of the gunfire I made out the unmistakable silhouette of The Loch Ness Monster.

"Over there…" he yelled above the cacophony, his arm waving into the night ."In the waddie…" Nessie had been something in the desert. Chad, I think. Hence his use of the term "waddie". It was a dip in the ground. "About twenty of the pigs,"

In French, he went on, "Can you work your way around back of them?"

I was not about to be drawn into a conversation in a foreign language. I could have done it, my French was pretty good. But I didn't feel up to it then. In English, I called, "Why can't you?"

It was meant as a joke. Sort of.

Nessie grunted. "Because I've got three wounded and two dead already! Don't ask stupid questions!" Then he called me a pig in French. He could make life damned difficult at times.

A mortar shell tore a great chunk out of the sky. It exploded only feet from where the helicopter had put down moments before. Someone screamed out in the darkness. It was bedlam. There seemed to be flashes coming from all around us now.

Nessie rammed his face right up to my ear. "They got Askaris with them. Can't shoot worth a damn, but they’re making a lot of noise. Can you do it?"

I didn't know. If Patch's patrol had Askaris, nothing was going to be easy. I was conscious that my section was grouped around us, kneeling there, waiting for some kind of leadership. I yelled, "What's the terrain like?"

A string of bullets zapped through the air over our heads, sounding like a horde of angry hornets. Nessie didn't even duck his head. You can be sure that I did! He explained that we were in a large clearing, bordered on one side by a river - which was invisible to me - and on the other by jungle. His "waddie" was just short of the tree line. Still with his lips hard against my ear, he went on to tell me that there was a track some seventy or so yards back into the trees, and that it was the track where he needed to be. Mainly, I gathered, because that was where his transport was.

He had been on his way to mine a bridge, and he felt the inclination to continue with that operation. The opposition, according to Nessie, was not aware of the track. Ergo, they did not know about the trucks.

I shoved my mouth to his ear. "Why'd you leave the trucks in the first place?"

He shouted. "Did you come here to ask bloody fool questions, or to give someone a hand!" That was in English.

It was a crazy, disjointed kind of war, with crazy, disjointed people fighting it. I called, "I suppose you've already tried to get in back of them…"

Another mortar shell exploded close by, and by the light of the flash I saw that Nessie was grinning. He yelled, "Bien sur!"

I guessed there were snipers out on the hidden flanks. I called. "Well, fuck you!" I didn't often swear.

He laughed. "Santana would do it for me!"

And he probably would have. I said, "But you didn't get Santana…you got me! If we take them at all, we take them head on!"

Nessie said shit in French. But he knew me as well as I knew him. He called, "Bon!...I'll take the left flank, you go down on the right. How many men have you got here?"

I said, "Enough to cover your deficiency, plus seven…Khan!" The latter to Ahmed Khan, the two-striper I'd designated 2i/c. One of the dark shapes grouped around us detached itself and came trotting over. "Yes, sir!"

Khan had been with the company when I arrived. But I had known him before, in Chile and other places. Indian mercenaries were not thick on the ground. The depths of my knowledge of Khan's private life, despite having worked with him before, was that he came from Poona. I didn't even know how old he was. What mattered to me was that he was solid, and not given to panic under fire. As he stood in front of me, waiting for his instructions, I spared a moment to figure whether or not we were doing the right thing, and in the right way.

But there seemed no other way to do what had to be done. As things stood - apart from the snipers - we knew where the enemy was: mostly static, and in a dip in the ground. In the dark, knowledge is a plus. And it was as dark for them as it was for us.

Nessie growled, "Vite, man, vite!"

I wondered why he was in such a rush.

To Khan, I said, "Fan out, to the near right. You've got a crater-full of enemy directly ahead, so go in fast and low. Friendlies on the left flank, snipers in the trees over on the right flank someplace, so watch it! We go on my whistle. Okay?"

Khan nodded and started to chivvy the men into some kind of order. Suddenly, for no apparent reason, all the shooting stopped. There was complete silence for several seconds, like someone had pushed a button. We stood there like idiots wondering what the hell was going on. The darkness, without the weird illumination of the gun flashes, was complete and utter. Then it started up again. But most of it was wasted effort, the hornets zipping through the air over our heads. I could see no flashes coming from the far right so, if snipers there were, they would be biding their time. This had a bad side and an even worse side; it meant that someone out there was really using his head.

Nessie called, "I want their C.O. alive. Tell your men!"

I sighed inwardly. Hidden agendas will be the death of us all. There was a whole lot of more important stuff to think about before considerations of that sort. I said, "What the hell d'you need him for?" I expected to be told not to ask any more stupid questions.

Instead, Nessie said, "I want to slit the pig's throat. He's held me up here for two fucking hours!" Only the "fucking" was in English.

I couldn't think of a suitable reply. So I ignored it. "We'll need a para-flare. Have you got any?"

Nessie said something in a guttural tone that I didn't catch, and probably wasn't meant to. Then he said, "You'll get your fucking flare…Now, can we get on with it!"

He was obviously in one of his dangerously-fearless moods. I refused to be rushed. "It goes up ten seconds after the whistle. Okay?"

Again, I didn't catch whatever it was he said. But it seemed an affirmative and there was only so long we could stand there arguing the toss. Either we did it, or we didn't. And the latter was not an option, certainly not in Nessie's book. So I blew the whistle. And in that instant my racing pulse slowed to a tick-over. This was me. This was what I was all about. Reasons didn't matter. The rights and the wrongs of it didn't matter. The stupidity of it all didn't matter. Not even the danger mattered. I was exactly where I needed to be. I was a stateless, worthless mercenary soldier doing what mercenary soldiers do.

This kind of Armageddon was my comfort zone. Everything else was just marking time. Sad, but true.

My first action under hostile fire, however, had been swamped with very different feelings. My whole body had trembled with blind fear and I could easily have voided myself. How I actually had not done that, I do not know. But I remember thinking that I should have stayed home with mother, if only she had still been alive at that time. I certainly had not wanted to be there, in that place, waiting for either the stray bullet, or the one actually aimed directly at me. It was a horrific feeling. But thankfully it had passed quickly. Like stage fright. I was never to experience those feelings again.

We charged into the strobe-lit night.

Khan was at my right shoulder when he caught a bullet square in his chest, but he eventually reached the waddie and sprayed hell out of the men who were using it as a firing pit. Palmer, a spotty-faced Australian, also caught a chest full and didn't make it two yards. Manfred Haug went down yelling, "Zeig Heil!" and he didn't get up again. Ron Pearce was another casualty. I don't know when he bought the farm. But buy it, he did. There's a lesson in there if you're clever enough to see it.

The first few seconds of a head-on assault are always the most expensive. You grit your teeth, duck and weave, and hope. You don't think. If you thought about the possibilities and the what-ifs, you wouldn't move.

"Salty" Stephens also made it to the waddie, but without so much as a scratch. He and a mortally wounded Khan stood there like rocks, their automatic weapons spitting death and destruction. I don't remember too much about what I did or how I did it but, I too, reached the waddie. I expended at least four full magazines during that brief onslaught. The flare was still in the sky and it was as bright as day.

Someone else - I was told later - whose name I did not know, apparently refused to move. He was the last of our relief section. Nessie, closest to the man, shot him in the head. I did not get a chance to ask Nessie why he had waited back there in the first place. But that, too, like his summary justice, would have been Nessie's style.

Someone over on the far left flank was using grenades. The flashes vivid yellow-red and evil-looking. I hate grenades. They're so damned impersonal. And their effect is unfathomable. Guys have been inches from an exploding grenade and come away without a scratch. Other guys have been many yards away, and had their heads blown off. With grenades you just never know.

Orestes Savas, nickname "Ori", a Mexican out of Curly's Dove-section, and a relative newcomer, plus a guy I only knew as "Chalkie" - last name White, I guess - were yelling like banshees as they went in. They both got through unscathed.

Donald Yelland, another American, got half his face blown away. Strangely, in the chopper, he'd asked me to post a letter for him if he bought it. For reasons now lost in time, I misplaced that letter. Not that I would have posted it in any case. I would have done that for Khan, however. Yelland fought on for a while. God alone knows how he managed to do that. But he did. Then, almost at the last gasp, he simply keeled over and was dead.

Alec "Maud" Peroni, the only homosexual in the outfit that I was aware of, caught a grenade splinter in his shoulder, but that was all. He was a reasonably good fighter, was our "Maud" Oddly, he had brought the nickname with him and seemed to use it proudly. I suppose it was better than wearing an "Actually, I'm gay!" badge on his chest. I don't know how he fared for partners, and I wasn't the slightest bit interested.

Al Schwarts, yet another American, was the medic. He remained where his job dictated he remain; bringing up the rear until needed. He bought it anyway. Someone with a very strong arm lobbed a grenade back there. One of the unknown snipers may have crept around on the far right flank. But it could just as readily have been one of our own. A larger or smaller percentage of casualties could always be laid at the feet of friendly fire. Such was unavoidable, especially at night.

Ying something-or-other, another Chinese merc out of Curly's Dove section, also got through it okay. He ran pretty damned quickly, but I don't think he lifted so much as a little finger towards the outcome. I determined to watch him like a hawk in future.

Nessie lost three more of his section.

All in all, it was an abnormally pricey half hour and Curly would be about due to send his men on another trip around the world in search of more unwitting volunteers. I hoped Nessie considered his bridge worth it.

What swayed it in the end, though, was that the remaining Askaris decided to throw in the towel. I guess sight of the chopper had impressed them. They were far too deep in the disputed territories to have the same possibility of reinforcement. Patch's guys, including the snipers who may or may not have occupied the flanks, just melted into the jungle and Nessie never did get to slit any throats. Not then, anyway.

Later, I asked Nessie why he hadn't simply called in the chopper and used it to get the hell out it. He just gave me a crooked smile and tapped the side of his nose. This made me think that he had booty of some kind stashed in the trucks. That would also be about his calibre. I did not bother to ask about the field-punishment thing. He would, actually, have been well within his rights.